What Were the Causes of Germany's Hyperinflation of 1921-1923

Among the defining features of early twentieth century Europe and one of the contributing factors to World War II, was the economic maelstrom known as “hyperinflation” that ravaged Germany from 1921 until 1923. Although the short period is often overlooked in popular histories of the period, there is no denying the impacts that the process had on Germany, Europe, and the world. Because of the hyperinflation of the 1920s, the effects of the later worldwide Great Depression were accentuated in Germany, which ultimately undermined the legitimacy – at least in the eyes of the German people – of the Weimar government. As the Weimar government attempted to fix the economy that was seemingly spiraling out of control, the German people turned to organizations on the far right and left wings of the political spectrum for answers. Despite eventually being able to end the crippling process of hyperinflation by 1923, the damage had already been done to Weimar government, which was living on borrowed time at that point.

In the nearly full century since Germany’s bout with hyperinflation, historians and economists have examined Weimar government records, private business reports, and anecdotal sources such as letters, in order to determine the extent of the process and ultimately how it began. Scholars have learned that Germany’s hyperinflation was actually quite a complicated process and there have been a number of factors identified as contributing to its origin. Essentially, all of the ingredients that went into creating Germany’s hyperinflation can be grouped into three categories: the excessive printing of paper money; the inability of the Weimar government to repay debts and reparations incurred from World War I; and political problems, both domestic and foreign.

Contents

Inflation and Hyperinflation

In order for one to understand the causes of Germany’s hyperinflation during the early 1920s, one must first understand how the process is related to and also different from a standard inflationary cycle. Simply stated, inflation is when the prices of goods rises, causing an imbalance in the money supply if it happens too quickly. During an inflationary cycle, there is too much money in circulation, which causes the currency to devalue and the prices of commodities to increase in proportion. Although the reasons for a typical inflationary cycle are complicated, most economists point toward excessive printing of money or other currency manipulation by the central banks – “Quantitative Easing” during the last recession would be an example of this – as the primary factor. Basic goods such as food and fuel are affected first, but eventually the process will influence the prices on everything. As troubling as inflation can be to an individual’s pocket book, or even an entire nation’s economy, it is nothing compared to the process of hyperinflation. The process of hyperinflation is when inflation continues to increase unabated until there is a 1000% in prices over the course of a year. [1] When the German economy transitioned from an inflationary to a hyperinflationary cycle in 1921, it was an extremely difficult burden for the average German to bear.

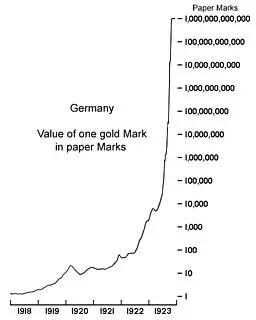

As the prices of goods soared at what were until then unimaginable levels, Germans increasingly found it difficult to purchase even the most basic items. For example, one loaf of bread coast twenty-nine pfenning when World War I began in 1914, but by the summer of 1923 that same loaf of bread cost 1,200 Reischsmarks and just a few months later, in November, the price had soared to an astronomical 428 billion Reichsmarks! [2] Because of the steep price increases Germans were forced to improvise in a number of different ways. Many would pay for meals as they ordered because the prices would increase significantly in the time it took to eat while others used the virtually worthless bills to heat their homes. All Germans, no matter their income level, had to devise ways to deal with the new economic reality.

The Causes of Germany’s Hyperinflation

As the average German struggled to survive during the crippling period of hyperinflation during the early 1920s, government leaders and economists searched for its cause in order to rectify the situation. They quickly found that there was not one single cause, but instead the cycle was brought forth by a number of contributing factors that combined to form a perfect storm of economic collapse. As noted above, the first place to look during any inflationary cycle is the amount of currency in circulation. In Germany’s case, one must first understand the historical context of the cycle. Before World War I, Germany was on the “Classical Gold Standard” system, which meant that all of its currency in circulation had to be backed by physical gold. Nations that were part of the Gold Standard – which included nearly every industrialized nation-state and their colonies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – generally saw very little inflation because the requirement to back all currency with gold placed restraint on the printing of money. Once the world entered World War I, though, the Gold Standard was quickly scrapped by countries that needed funds to pay for their war efforts. Germany was one such nation.

To fund its war effort, the Imperial German government incurred a 150 billion mark debt. It also began a policy of excessive currency printing so that by the end of the war there was six times more money in circulation than when the war began. [3] Once the war was over, the new German government – commonly referred to as the “Weimar” government for the capital it chose – continued the policy of excessive printing in a move to manipulate its currency in order to help the struggling economy. Weimar economists theorized that devaluing their currency would help Germany’s industrial sector rebuild because the prices of its exports would be more attractive to foreign investors. Foreign investors could simply buy more German exports with their own currency, which was worth much more than the Reichsmark. [4] The economists were correct in that German exports temporarily increased, but they failed to consider the plethora of other factors that were driving the inflationary cycle.

As one of the “losers” in World War I, Germany was forced to pay exorbitant reparations to the “winners,” primarily France and Belgium, for the damage done to those countries. The reparations payments, which were putative more than anything, resulted in an adverse balance of payments in Germany. The Weimar government, as well as German corporations, had difficulties obtaining credit abroad to fund industries that could inject money into the economy needed to make the payments, which combined with a loss of territory under the Treaty of Versailles, meant that Germany needed to import more raw materials to keep its industry going. The result was a further devaluation of the Reichsmark. As with the domestic debts it incurred from the war, the German government saw devaluation of the currency as a viable option, but the reality was that it gave itself little room for economic maneuvering. [5]

The fiscal corner that the Weimar government found itself in as the result of wartime debts incurred by and reparations forced upon the previous government, was further exacerbated by its own leaders’ inability to grasp the complexity of the situation that was rapidly unfolding. The Weimar government became extremely myopic and was plagued with what seemed to be eternal gridlock in the halls of the Reichstag (the German parliament). The left and right wing parties were nearly equal in the Reichstag in 1921. To many people today, this may seem like the optimal form of “checks and balances,” but in early 1920s Germany it resulted in political stalemate where neither side was willingly to give ground. Among some of the most fundamental issues that neither side could agree upon was the need to raise taxes for social services, such as the payment of military pensions for veterans. In order to rectify the situation, the government decided to print more money, which in turn devalued the already plummeting Reichsmark. The inability to provide for basic social services with non-inflated currency stemmed from the Weimar government’s inability to grasp the scope of the situation. Officials and economists in the Weimar government viewed Germany’s economic woes through the lens of the nineteenth century instead of seeing it as it really was – an economic process taking place within a complex system that was integrated with the economies of the other industrialized nations. [6]

The final nail in the German economy’s coffin of the early 1920s was actually two unforeseen events that took place both inside and outside of Germany’s borders. The first event was the assassination of German foreign minister Walther Rathenau in June 1922. The assassination caused political panic in the increasingly unstable Germany and set off a speculation crisis that saw the Reichsmark plunge in value on world currency markets. Rathenau’s assassination was followed by the occupation of the Ruhr Valley by French and Belgian military forces in January 1923. The French and Belgian governments hoped that by occupying the mineral and industrially rich Ruhr Valley they could force the Germans to make reparations payments; but the occupation had the opposite effect. The occupation of the Ruhr further crippled industrial output, which in turn devalued the German currency even more. By November 1923, the Reichsmark was worth only one-trillionth of its pre-World War I value. [7]

The End of the Cycle and Its Results

Although Germany’s bout with hyperinflation was a gradual process and took a while to peak, it ended rather quickly. After numerous failed attempts to alleviate the process, the Weimar government introduced a new currency known as the Rentenmark in 1923. Unlike the Reichsmark, which was not backed by gold or any other tangible asset, the Rentenmark was back by real estate. When the Rentenmark was first introduced in October 1923, one bill was worth an astonishing one trillion Reichsmarks! [8] Although the Weimar government was able to effectively end the hyperinflation by the end of the year, the damage had already been done to the German economy, political system, and greater society.

Among the many different groups who suffered due to the hyperinflation and never were really able to get back on their feet, were members of the German middle class. Middle class workers and small business owners were especially hit hard when they saw their savings evaporate overnight. [9] Many middle class retirees found themselves back at work and many others had to rely on the goodwill of friends and family just to make ends meet. All of this resulted in a loss of confidence in the Weimar government, which was further exposed as being weak and ineffective when Germany had a brief economic Depression in 1925-26. Despite the hardships that hyperinflation caused in Germany, there were some who were able to profit from it.

There are always people who prosper during times of economic distress, even during a near collapse. In the case of Germany’s hyperinflation, people who were in debt came out ahead since the amount owed on any debt only increases due to interest rates; debtors were able to use inflated currency to quickly pay off their debts. Those with a keen sense of business acumen quickly picked up on this and took out loans to buy items of real value – real estate, gold, and artworks for instance – which they were then able to quickly turn into profit. Stock market speculators and exporters of German goods also came out ahead financially once the smoke of the hyperinflation cleared in 1923. [10]

Perhaps the biggest beneficiaries of Germany’s hyperinflation, though, were the far rightwing and leftwing political parties and paramilitary organizations. As the Weimar government appeared to be unable to deal with the economic problems of the 1920s, more and more Germans began turning to extreme organizations for answers. Rightwing paramilitary groups such as the Freikorps engaged in armed battles with communist organizations like the Spartacus League on the streets of nearly every major German city during the 1920s, which left hundreds dead by the end of the decade. [11] Eventually, the National Socialist German Worker’s Party presented itself as a viable alternative to what it described as a weak and degenerate Weimar government.

Conclusion

The period after World War I was an extremely critical juncture in world history where the stage was set for World War II. Among the most important factors that led to World War II, albeit indirectly, was the hyperinflationary cycle Germany experienced from 1921 through 1923. During that period, the Weimar government watched as prices soared over 1000% and sat helplessly as its currency essentially lost all of its value. The factors that contributed to that short but devastating cycle can be attributed to excessive printing of currency, the inability to pay off wartime debts and reparations, and a couple of major political events. Although the Weimar government was eventually able to quell the hyperinflationary cycle, the German people lost confidence in the government and so began looking elsewhere for political answers.

References

- ↑ Widdig, Bernd. “Cultural Dimensions of Inflation in Weimar Germany.” German Politics and Society 32 (1994) p. 11

- ↑ Widdig, p. 11

- ↑ Widdig, p. 10

- ↑ Rickards, James. Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Global Crisis. (New York: Penguin, 2012), p. 57

- ↑ Laidler, David E., and George W. Stadler. “Monetary Explanations of the Weimar Republic’s Hyperinflation: Some Neglected Contributions in Contemporary German Literature.” Journal of Money 30 (1998) p. 819-20

- ↑ McNeil, William C. “Weimar Germany and Systematic Transformation in International Economic Relations.” In Coping with Complexity in the International System. Edited by Jack Snyder and Robert Jervis. (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1993), p. 193

- ↑ Overy, Richard. The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Third Reich. (London: Penguin, 1996), p. 130

- ↑ Widdig, p. 11

- ↑ Widdig, p. 12

- ↑ Widdig, p. 12

- ↑ Rickards, p. 76