Difference between revisions of "How Did Southern Belles Help Dispel Their Own Stereotype"

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | [[Category:Wikis]] [[Category:Civil War]] [[Category:Medical History]] | + | [[Category:Wikis]] [[Category:Civil War]] [[Category:Medical History]][[Category:United States History]] |

{{Contributors}} | {{Contributors}} | ||

Revision as of 04:37, 31 March 2018

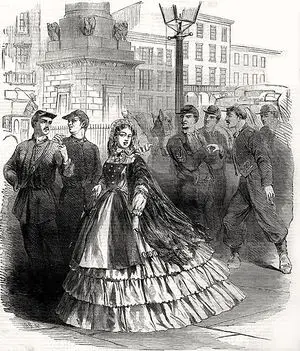

In all of 19th century America, with the exception of various indigenous tribes, women were seen as the weaker sex. Circumstances had changed to a certain degree in the northern states, due in part to the increasing migration to cities. Whereas the North was becoming more conducive to urban living, the agrarian lifestyle remained strong in the South. While women in the northern states ventured into politics, social causes, and ultimately independence, young ladies in the southern part of the country had no need to engage in labor.

The Antebellum South was constructed and rationalized from stereotypes. All too familiar are the stereotypes of African-Americans being seen as barbaric, lazy, and ignorant. Equally strong in the South was the stereotype of the "Southern Belle." The belle was perceived as a woman of culture and refinement. Although this myth was in fact perpetuated by the actions of elite white women, the tenacity and strength displayed by several of these ladies during the Civil War crisis forever changed public perception. Southern women of the elite class worked incredibly hard and toiled long hours with the hope of restoring the South to its antebellum state. Ironically, by doing so they aided in dispelling the myth of the Southern Belle.

Antebellum Women

The life of a plantation mistress was constructed to be one of leisure. Unlike their counterparts in the North, young ladies in the South had no opportunities to earn wages on their own, thus the only means by which to leave the family home was through marriage. Young women in the northern states; however, were entering the work force in factories and the textile mills of Lowell, Massachusetts as early as the 1820’s and were able to enjoy a feeling of independence.[1] In Southern culture, women devoted their time to leisure and the pursuit of culture; labor was for slaves.

The plantation wives held charge over the domestic slaves and often found room to complain about the task of maintaining obedience. In a diary entry from February of 1861, wealthy South Carolinian Ada Bacot grumbled that some of her “young Negroes have been disobeying my orders.” Her journal entry continued to say that she was “mistress and will be obeyed.”[2] The only authority a southern women was able to exert at the time, was over slaves. Less than two years later, Mrs. Bacot would find herself working as a Confederate nurse in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Bacot arrived in Charlottesville on December 12, 1860. She was a strong and vocal secessionist who compared her love for South Carolina to that of “an affectionate daughter for a mother.”[3] She was willing to endure the hardships of a hospital in order to preserve the culture and societal norms of her state. Nursing and other hospital services up until this time were considered to be the domain of men. The Confederate Army Medical Department was created on February 26, 1861 and was overseen by the Confederacy’s first Surgeon General, Dr. Samuel Preston Moore.[4] The hospital attendants consisted of slaves and enlisted men who were deemed unfit for service. As a general rule, men were essentially ignorant as to the methods of caring for the sick and wounded. The medical director in Danville, Virginia described his male nurses as “rough country crackers who have not enough sense to be kind.”[5]Conversely, women were somewhat skilled in caring for the sick as they had done this on the home front prior to the war. In September 1862, the Confederate Congress passed an act allowing hospitals to hire two matrons and two assistant matrons and as many cooks and nurses as needed. Those who were tasked with hiring were instructed to give “preference in all cases to females.”[6]

Breaking the Stereotype

Many belles responded to the call with a sense of duty and pride, while an even greater number deemed this type of work to be unfit for a lady. Kate Cumming, a dedicated Confederate nurse, recalled being told that the hospitals were no places for women and that was not considered “respectable to go into one.”[7] In April 1862, Cumming arrived in Corinth, Mississippi at a hotel that had been converted into a hospital. She was initially unaware of the sights, sounds, and smells she would encounter and confessed to her journal that the “foul air” made her “giddy and sick,” and that it was necessary for her to “kneel, in blood and water.”[8] Circumstances such as these were in stark contrast to anything these women experienced in the Antebellum Era.

The levels of care and sanitary conditions varied from hospital to hospital. Cleanliness was continually emphasized as the medical directors were well aware of the prevalence of disease and infection. The most common symptom upon arrival at any hospital was dysentery. A soldier's life in camp was conducive to this problem as water sources were contaminated by human excrement. The southerner men who arrived in camp from rural areas were what one might call "rubes." They had little experience with community latrines or education with regard to proper sanitary procedures. Unfortunately, these poor hygienic practices were continued when the soldier arrived at a hospital. For example, Jackson hospital in Richmond was described as having the “floors and seats of sinks…smeared with excrement.”[9] These foul examples of sights and smells offer just a glimpse of what the nurses had to endure; the emotional impact was equally great.

Interactions with the Wounded

After being wounded in battle, Alexander Hunter was treated at a Petersburg hospital. He briefly described rows of “extended wasted figures burning with fever and raving from the agony of splintered bones,” and the “sickening odor of medicine, the nephritic air shut in by the closed windows.”[10]Confederate nurses dealt with these sights, sounds, and smells daily. Phoebe Yates Pember recounted a particularly horrific scene after the Union army broke through at Petersburg. Once the Yankee Army took Petersburg, they cut the rail service, which was the only viable source to rapidly transfer patients to the Richmond hospital, Chimborazo. After this horrific fight, Lees’ army retreated and was forced to leave the dead and wounded on the battlefield. Three days hence, these wounded men arrived at Chimborazo, where Yates was superintendent. She spied a man with a heavily bandaged head who was left sitting unattended. She immediately tended to him and upon removal of his bandages she was left gazing at a horrific sight. This man had been shot twice in the face, wherein the musket balls penetrated his jaw and cheek. His teeth were missing and half of his tongue had been severed. Upon closer examination she noted the “swollen lips turned out, and the mouth filled with blood, matter, fragments of teeth from amidst all of which the maggots in countless numbers swarmed and writhed, while the smell generated by this putridity was unbearable.”[11]

Pember, who began work at the hospital in December 1862 and stayed until her patients were transferred to federal units in April 1865, stated she would never forget that sight. She, like her peers, tended to adopt favorite patients and took it especially hard when they died. While holding pressure on the severed femoral artery of a soldier named Fisher, the young boy asked, “How long can I live?” Pember replied, “Only as long as I keep my finger upon this artery.” As tears filled Phoebe’s eyes, Fisher said, “You can let go.”[12]Fisher, and so many others like him, filled the hearts and memories of these women for the remainder of their lives. They were no longer pure and unscathed ladies of refinement. Like the soldiers who witnessed battle, these women, like their Yankee counterparts, were also haunted by the emotional scars of war.

Yankee Nurses

When first offered the job of superintendent at Chimborazo, Pember thought it was a “startling proposition to a woman used to all the comforts of luxurious life.”[13]Pember and many other women of this ilk soon uncovered the strength which they were endowed. Women of the North had grown more confident by exerting their strength and as a result had become quite outspoken with regards to politics and social issues. They also hastened to join the nursing corps at the outbreak of war and quickly put their organizational skills to work. Dorothea Dix was appointed superintendent of female nurses by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton on June 10, 1861.[14]Prior to that, she worked tirelessly for prison reform and was a devoted advocate of the insane. In addition to these endeavors, she founded and established thirty-two hospitals.[15]

Bostonian Mary Livermore, was a well-educated teacher and active with the temperance movement. Prior to the war, she had taken charge of a school in southern Virginia, where she was first exposed to slavery. She returned to Boston as a “radical abolitionist.”[16]Soon after, she went to Illinois with her husband and was the only female reporter present at the Lincoln nomination in 1860. Taking her intelligence and skills forward, Livermore helped in the organization of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, where she traveled among the vast network of Union hospitals during the war.

Perhaps the most charismatic of all the Union nurses was Mary “Mother” Bickerdyke. Her service with the Union Army began at the Battle of Fort Donelson in February 1862, and concluded with General Sherman as he marched through Georgia and the Carolinas. This remarkable woman took it upon herself to trudge through the battlefields at night with a lantern in an attempt to identify signs of life in any of the fallen soldiers. She was a widow in her forties and commanded respect and affection, not only from “her boys,” but from General Sherman himself.[17]

Conclusion

While Dix and Livermore were actively pursuing social reform and education during the 1840’s, Mrs. Virginia Clay of Tuscaloosa, Alabama was attending balls. She described scenes of “belles of the town” looking “resplendent in fresh and fashionable toilettes.” Twenty years hence, Phoebe Yates Pember, who was of the same social standing as Mrs. Clay, was holding her finger on a man’s artery in order to keep him alive. While women on the plantations complained about disciplining their slaves, nurses were dealing with the rowdiness associated with hundreds of young men being confined together. According to Kate Cumming, “the most unruly and dastardly in our hospitals have been from Louisiana.”[18]

These women worked tirelessly to help their cause and to comfort the young men of the Confederacy. Although their previous work experiences did rival their counterparts in the North, these courageous women eschewed decorum and sacrificed their comfortable lives in order to care for the wounded and make the last moments of the dying more tolerable. What they witnessed no longer allowed them to be belles. They were no longer pure and meek. During the course of the war, Chimborazo hospital alone treated 77,889 patients. Throughout the entire war, there were only 1,000 female Confederate nurses. Given these numbers, we get an idea of how tirelessly these women served. They were doing the work of women, not the work of belles.

References

- ↑ Ellen Carol DuBois and Lynn Dumenil, Through Women’s Eyes: An American History (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2005), 149.

- ↑ Ada W. Bacot, A Confederate Nurse: The Diary of Ada W. Bacot, 1861-1863, ed. Jean V. Berlin (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1994), 27.

- ↑ Bacot, 25-26.

- ↑ Carol C. Green, Chimborazo: The Confederacy’s Largest Hospital (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2004), 3.

- ↑ H.H. Cunningham, Doctor’s in Gray: The Confederate Medical Service (Gloucester: Peter Smith, 1970), 72.

- ↑ Green, 44.

- ↑ Kate Cumming, quoted Cunningham, 73.

- ↑ James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 479.

- ↑ Cunningham, 88.

- ↑ Cunningham, 93.

- ↑ Phoebe Yates Pember, A Southern Woman’s Story: Life in Confederate Richmond (Jackson: McCowat-Mercer Press, 1959), 88.

- ↑ Pember, 67-68.

- ↑ Pember, 25.

- ↑ Mary Gardner Holland, Our Army Nurses: Stories From Women In The Civil War (Roseville: Edinborough Press, 1998), 1.

- ↑ Holland, 76.

- ↑ Holland, 165-66.

- ↑ Holland, 25-26.

- ↑ Cunningham, 91.

Admin, Costello65 and EricLambrecht