How did the Bubonic Plague make the Italian Renaissance possible?

The Black Death (1347-1350) was a pandemic that devastated Europe and Asia populations. The plague was an unprecedented human tragedy in Italy. It not only shook Italian society but transformed it. The Black Death marked an end of an era in Italy. Its impact was profound, resulting in wide-ranging social, economic, cultural, and religious changes.[1] These changes, directly and indirectly, led to the emergence of the Renaissance, one of the greatest epochs for art, architecture, and literature in human history.

What was the Impact of the Plague in Italy?

To Black Death spread to Italy from modern-day Russia. Genoese merchants spread the plague while fleeing a Mongol attack on their trading post in Crimea. The plague was carried and spread by the fleas that lived on the Black Rat and brought to Italy on the Genoese ships.[2] The population of Italy was ill-prepared for the spread of the disease. There had been a series of famine and food shortages in the region, and the population was weak and vulnerable to disease. Furthermore, the population did not have any natural resistance to the disease. Italy was the most urbanized society in Europe, Milan, Rome, Florence, and other Italian centers among the largest on the continent.[3]

The majority of the urban population in Naples was impoverished and lived in squalid and dirty conditions. These factors ensured that the diseases spread quickly and that there was a high level of mortality among the poor, although even the rich could not escape the plague.[4] From the cities, the plague spread like wildfire to the small towns and villages of the peninsula.

There is no firm data on the impact of the plague on the population of Italy. However, some examples show the full extent of the disease in Italy. The plague halved the population of Florence. The population crashed and fell from approximately 100,000 to 50,000. Florence's experience was replicated across all the major cities of Italy, which also experienced similar drastic declines. The death rate in rural Italy was not nearly as high, but there was a significant loss of life. In general, the total population of Italy may have dropped by as much as a third.[5]

The Black Death was also an economic crisis as trade ceased because of fear of the plague spread. As trade stagnated, businesses failed, and unemployment rose. The plague caused a complete social breakdown in many areas. In the Decameron, Boccaccio describes people abandoning their occupations, ignoring the sick, and living lives of wild excess, as everyone expected to die.

"Thus, doing exactly as they prescribed, they spent day and night moving from one tavern to the next, drinking without mode or measure, or doing the same thing in other people's homes, engaging only in those activities that gave them pleasure….. And they combined this bestial behavior with as complete an avoidance of the sick as they could manage."[6]

Socio-Economic Consequences

The social consequences of the plague on society came to be profound. The high mortality rate resulted in a drastic decline in the labor force.[7] Wages rose for both agricultural and urban workers. The survivors of the Black Death generally had a higher standard of living than before the plague.[8] This phenomenon occurred in both urban and rural areas. The crisis caused by the Black Death led to many changes in the economy in response to the fall in the population. Because of the labor shortages, there was a move from labor-intensive farming such as cereal to livestock and an increase in industry and agriculture more labor-saving devices employed.[9] The impact of the Black Death was contrary to feudalism in Italy. Feudalism was a system whereby peasants and farm laborers were bound, as serfs, to serve a local lord. In the north of Italy, good farmland was plentiful, and wages increased, and the last vestiges of feudalism disappeared as serfs increasingly could purchase their freedom.

In the south of Italy, the opposite occurred. Here, since the Norman kings, the aristocracy had been consolidating feudalism. After the Black Death, the elite responded to the labor shortages by strengthening the peasants' restrictions and thereby strengthened feudalism in southern Italy. The plague's consequences resulted in a growing divide between the North and South of Italy that persists to this day.[10] In general, after a period of recovery, much of Italy became very wealthy as a more sophisticated economy emerged, especially in the North of Italy. This was crucial, as Italy's increased wealth allowed the elite, such as the De Medicis in Florence, to become the patrons of great artists such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci.[11]

Religious Consequences

Initially, in Italy, the plague led to a revival in religion among many. The middle ages was a time when people believed that events are a result of God’s will. Many viewed the plague as punishment for God for the wickedness and immorality of the people. There was an upsurge in religious observance, and many sections of the public became swept by religious fervor, as many sincerely believed that the Black Death was a sign that the end of the world was coming.[12] Religious fanaticism spread throughout the peninsula and many men and women performed in extreme religious practices, such as the flagellants. The flagellants whipped themselves into a frenzy to atone for their sins. The Church suffered greatly during the plague. Many priests and especially monks died. The monasteries proved ideal breeding grounds for the plague while many priests contracted the sickness as they gave the dying's last rites. [13]

The result was a shortage of trained monks and priests. To deal with this, the Church hastily trained new monks and priests to serve the community's spiritual needs, still coming to terms with the trauma of the Black Death. This meant that many unsuitable individuals became clerics, which led to a drop in standards among parish priests, in particular.[14] The Church became corrupt and gradually over time lost the respect of many believers. In the short term, the Black Death strengthened the Catholic Church in Italy, but an increasingly corrupt institution meant that many people lost their faith in the long run. This led to the increasing secularisation of Italian society as many increasingly turned away from the church in disgust with prelates and priests' worldliness. Many felt contempt in Boccaccio's stories of venal and depraved priests, monks, and nuns.[15] The church had traditionally monopolized education, but after the Black Death, there was more secular education, especially in the cities. This was decisive in the emergence of the Renaissance, emphasizing human values and experiences rather than religion.[16]

Questioning of authority

The world was turned upside down by the Black Death. The mental outlook of people changed dramatically. Previously, people assumed that the world was fixed and God-ordained. The Black Death overturned old certainties. As we have seen, the plague and its devastation undermined religious orthodoxy and beliefs. People at the time were no longer willing to accept the status quo. This change manifested in the numerous political revolts of the time.[17] The most famous of these, led by the poor workers and weavers called the Ciompi popularly, took place in Florence in 1378. For four years, the poor formed the government of the city. The revolt was one of several in Italy at the time. People are no longer willing to question the old ways of doing things and no longer accepted things because they were sanctioned by tradition.

The Black Death led to a great questioning of the old certainties. This led many, especially among the urban elite, to use reason to understand the world. They also increasingly turned to the classics to find answers to the problems of life. The new spirit of inquiry helped to ignite the Renaissance, especially in politics and philosophy.[18] However, that is not to say that Italy rejected all traditions. It was still a very conservative society in many ways. However, those who questioned authority and the received wisdom, such as the Poet and Scholar Petrarch, inspired the Humanist movement, which valued reason and critical thinking. The Humanist is essential in the development and progress of the Renaissance.[19]

Cultural Change

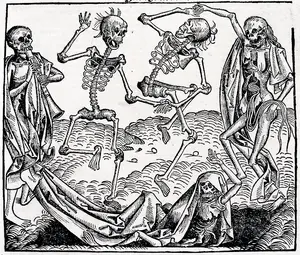

Initially, the Black Death led to a fascination with death among many Italians. The loss of life and suffering led many to become obsessed with death.[20] The Dance of Death was a popular motif in art and architecture at this time. The general mood was one of pessimism, and indeed many expected that the world would end sooner or later. Alongside this fear of death and the general mood of pessimism, there was a desire to experience the pleasures of life and seize any happiness on offer. This contradictory impact of the Black Death on the culture of the time can be seen in the writings of two of the greatest figures in European literature, Petrarch and Boccaccio.[21] These two writers at times wrote in despair about the human condition yet they also wrote about the joys of life and the beauties of nature.

This sense that life was fleeting and that every happiness should be seized led many Italians to seek solace in art and literature, and this was one of the factors in the development of the Renaissance. Many of the elite were eager to enjoy life's pleasures, which led them to patronize artists. It also resulted in a shift in the themes of artists.[22] Religious topics remained popular, however, there was also a fascination with secular themes, especially from the classical world. The new interest in secular subjects can be seen in a comparison between Giotto and Botticelli. Giotto painted almost exclusively religious paintings. While Giotto painted secular and religious themes, he is best known for his secular works as in masterpieces such as Primavera.[23]

Social Mobility

The plague disrupted society to an unprecedented state. It overturned the existing social structure. Previous to the outbreak of the plague, Italy was a rigid and stratified society. The Black Death changed everything. Increasingly, because of the plague's demographic disaster, they were able to take advantage of the opportunities caused by the high death rate. In the period after the Black Death, an unprecedented amount of social mobility took place. Laborers became merchants, and merchants become members of the nobility. No longer was a person’s destiny to be fixed by their birth. Previously, people assumed that one’s station was fixed at one’s birth and that one had to remain a member of the class you were born into.[24] People believed that a peasant would always be a peasant, an aristocrat, and an aristocrat. Italians, like other peoples, in Europe, believed that one’s birth determined one’s future and that this was determined by God.[25]

However, as social mobility became more widespread because of the Black Death, many people believed that a person’s merits or abilities were what mattered and not one’s birth.[26] This led to a growing individualism in Italian society. This, in turn, encouraged people to strive and develop their talents and achieve excellence or virtue.[27] The individual's belief was central to the Renaissance and inspired many of the greatest artists, architects, sculptures and writers, the world has ever seen to create peerless works.

Related DailyHistory.org Articles

Decline of the Nobility

One group that was adversely impacted by the Black Death was the nobility. This was also the case in many other European regions and kingdoms. The nobility suffered as much as many other classes due to the plague, and many families died out during the period. In the aftermath of the epidemic, they found themselves in serious financial difficulties. The loss of population meant no longer a high demand for their land, and rents fell.[28]

Many of their laborers left the land, and they were not replaced. Many of the nobility found themselves obliged to sell their serfs their freedom or to sell land to merchants from the cities. At this time, many wealthy merchants purchased new estates. The demise of the traditional elite meant that a new elite came to the fore, composed of merchants and self-made men. This new elite often keen to patronize arts. They were very conscious of their lack of birth and humble origins.[29]

They were keen to use art and to patronize scholars to compensate for the lack of traditional authority. To appear the equal of the old aristocracy, they sought to sponsor artists who would win the public's esteem.[30] This was one reason for the de Medici's lavish patronage in Florence. They were keen patrons of the arts to justify their status in society and impress the general population. This meant that the great artists had many patrons who often competed for their talents, which allowed them to concentrate on their art and produce some of the greatest art ever known.[31]

Who benefitted from the Renaissance in Italy?

While the Renaissance may have laid the foundation for broad changes in Europe over the long term, Italy's wealthy were the primary people who benefitted during the Renaissance. While wages for agricultural workers increased after the plague arrived, wages did not increase throughout the Renaissance. Additionally, in Florence, life expectancy declined for people during the Renaissance. Wealthy Italians during the Renaissance did clearly did benefit. Their wealth essentially funded the era's artistic achievements, but most Italian peasants probably would have preferred higher wages rather than the Mona Lisa.[32]

Conclusion

The Black Death devastated Italian society in the middle of the 14th century. It led to great socio-economic, cultural, and religious changes. After the initial horrors of the plague, Italian society staged a spectacular recovery. Italy became richer than before. The plague's impact reduced the influence of the Catholic Church as diminished, and the culture became more secular. The new social mobility meant that individualism came to be respected. The Black Death unleashed the forces in Italian society that made the Renaissance possible.

References

- ↑ Burckhardt, Jacob (1878), The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, trans. S.G.C Middlemore, p. 14.

- ↑ Pullan, Brian S. History of early Renaissance Italy: From the mid-thirteenth to the mid-fifteenth century (London: Allen Lane, 1973), p. 76

- ↑ Pullan, 1973, p. 89

- ↑ Andrew B. Appleby's "Epidemics and Famine in the Little Ice Age." Journal of Interdisciplinary History. Vol. 10 No. 4., p. 56

- ↑ Pullan, 1973, p. 156.

- ↑ Boccaccio, Giovanni. The Decameron. (Penguin Classics, Hammondsworth, 1987) trans Mark Musa, p. 6

- ↑ Hay, Denys. The Italian Renaissance in Its Historical Background. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,1997) p. 19

- ↑ Hays, 1997, p. 78

- ↑ Pullan, 1997, p 145

- ↑ Benedictow, Ole Jørgen Black Death 1346–1353: The Complete History (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press,2004) p. 234

- ↑ Frederick Hartt, and David G. Wilkins, History of Italian Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2003), p 67

- ↑ Benedictow, 2004, p. 234

- ↑ Benedictow, 2004, p. 234

- ↑ Hays, 1997, p. 178

- ↑ Boccaccio, 1987, p 67, 113

- ↑ Benedictow, 2004, p. 134

- ↑ Benedictow, 2004, p. 174

- ↑ Ruggiero, Guido. The Renaissance in Italy: A Social and Cultural History of the Rinascimento (Cambridge University Press, 2015), p 648

- ↑ Burkhardt, 1878, p. 67

- ↑ Herlihy, D., The Black Death and the Transformation of the West (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997) p. 116

- ↑ Benedictow, 2004, p. 173

- ↑ Pullan, 1973, p. 173

- ↑ Hayden B. J. Maginnis, Painting in the Age of Giotto: A Historical Reevaluation(Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1997), p. 78

- ↑ Benedictow, 2004, p. 73

- ↑ Pullan, 1973, p. 123

- ↑ Benedictow, 2004, p. 174

- ↑ Burkhardt, 1878, p. 78

- ↑ Pullan, 1973, p. 123

- ↑ Pullan, 1973, p. 23

- ↑ Burkhardt, 1878, p. 78

- ↑ Hayden B. J. Maginnis, 1997, p. 167

- ↑ Eleanor Janego, "Don’t kid yourself. The Black Death’s aftermath is not causing for optimism about covid-19." Washington Post, April 14, 2020.

Updated January 12, 2019 Admin, EricLambrecht and WDouglas